Okay so two things before we get started today. First, this has a part one in the title not because I am planning another series, but because media literacy is a big topic I may want to revisit in the future and am covering my bases because we are absolutely not going to hit everything worth talking about in one article. Second, I tried. I swear to God I tried to avoid dipping into Starship Troopers discourse when I was writing this, but it was impossible not to at least imply it as a key example in the argument, so I said screw it and just included it directly.

So with that out of the way, let’s talk about media literacy for a few minutes, shall we? Whether we like to acknowledge it or not, works of fiction have four purposes; and any work can have any of these four purposes in tandem or just one. These purposes are: To Entertain, To Inform, To Explore, and To Espouse. The first two purposes are obvious enough; entertainment is entertainment, and you can be taught or informed by pieces of fiction containing real world information. Even if the entire work is fiction, that dumb horror movie might accurately depict/explain a real world legend as part of its backstory, which means it informed its audience of that legend. Exploration is often the task of speculative works, primarily science fiction; this is when the goal is to present and explore a concept as much as possible. For example, Asimov’s Foundation trilogy explores how a society might defend itself against aggressive neighbors without having a standing military, while I Have No mouth and I Must Scream explores a potential consequence of a supercomputer built for war. Both of these stories have other purposes as well; they’re certainly each entertaining in their own ways. The fourth purpose is the one that’s grown controversial in recent years, as if it’s not the primary purpose of many beloved stories. To espouse is to talk to your audience, perhaps to impart a lesson, perhaps to discuss philosophy, perhaps to lecture the reader on a point. In other words, these include, but are not limited to, the works that get political. You’re readily familiar with these even if you avoid political works. Fairy tales are usually works that espouse, such as how every culture has a story about a woman (or occasionally a fiddler or a horse) who drowns you, which is meant to teach children not to go into the water alone for their own safety. Even this article is ultimately meant to espouse, since I’m talking directly to you about an issue I have opinions on as I write this.

This is important to understand, because these four purposes, often working together, leak directly into the vast majority of media. If you don’t believe they can work together to make a good piece of fiction, then look no further than the universally beloved movie from 1986, Aliens. The film is entertaining, it informs the audience that a technological advantage is not a flat victory condition in warfare, it explores science fiction concepts such as the morality of androids, and it serves as both a political critique of the US military during the Vietnam War and a subtle discussion on prejudice. If you didn’t catch those last points watching the movie, then I encourage you to revisit it and see both the way the cocky and more advanced military ignores warnings and gets dismantled by a weaker guerilla force (something the film’s director has talked about), and how Ripley’s previous experiences with an android prove wholly inaccurate to determining how the new android she’s asked to work with will behave. You’ll find the same four purposes in everybody’s favorite 2023 movies, Barbie and Oppenheimer, even if exactly what is being espoused varies. You’re smart enough to figure out how both of those touch on the four purposes, so I’m not going to lecture you on the answers.

Now that we’ve established that any piece of media can contain these four purposes, we need to talk about your role as the consumer. Not only do you as a consumer and member of the audience wish to understand the works you engage with, you also have a duty to understand what you are consuming. I’ve commented before that advertising and propaganda work, and as any media can be made to espouse, you should be aware of what you engage with and what you take away from it. I will never tell you not to engage with a work, regardless of what it espouses, because I sincerely believe that these works can, regardless of their intents and creators, have value. Even something written by the worst person can have value in allowing you to explore and understand the ideas of another side. And if those values espoused are truly vile? So long as you actively think about it and understand what you are engaging with, you can recognize what is there and take choose what you are consciously accepting into your mind. Part of the reason we need to hammer this point in is that there’s been a big push online recently to suggest that you can’t write about something without endorsing it. This should obviously be wrong, because a depiction can be used to condemn or discuss an action without condoning it, exploring characters who do bad things can make for engaging stories, and the audience should be trusted to examine a work and decide what is good and bad in it.

Part of why this push exists, I believe, is the fact that people can miss the point of a work. You’ll often here about people who love movies like Fight Club, American Psycho, or The Wolf of Wall Street because of how cool the protagonists are. Anybody who has thoroughly engaged with these works will realize that the three films condemn their central characters, and that we as an audience are not meant to side with them (if you want a literary example, Lolita is the most famous case of an untrustworthy narrator for a reason). The difficulty comes from the fact that in a well-written story that espouses values, you want to avoid directly speaking to the audience and saying, “X is wrong and you’re a bad person if you do it.” Show, don’t tell, is a universal piece of writing advice for a reason. However, when you show things without directly stating they are bad, there is an inherent risk that members of the audience will miss the point by not engaging as critically as the work intends. My favorite example of this is people quoting Taxi Driver’s “you talkin’ to me” scene to look tough when the actual context of that scene is meant to make the speaker look pathetic.

Ultimately, we have to trust the audience to understand a work. We as storytellers do the best we can to communicate our points organically (or inorganically, in the case of some less than talented writers), but different members of the audience will, regardless of original intent, interpret the same work differently. If we don’t then we become book burners who feel the need to hide anything that could ever be misinterpreted. We become the villagers from A Series of Unfortunate Events who do not know their own laws, because they destroyed the books explaining the laws for depicting examples of people breaking them and suggesting that it was possible to do something illegal.

I’m obviously doing an awful job of not telling right now, but that’s because this is an article written for the express purpose of talking directly to you, not a movie that’s also meant to entertain. Exactly what a work communicates, and how, changes depending on what medium is used to convey the point. A movie communicates a point differently than an article, which is different from a book, which is different from a game. And that’s wonderful, because it means there are stories that can only be properly told, points that can only be properly made, in certain forms of media. House of Leaves is a famous book that could never possibly work if converted into a movie or TV series, because the exact arrangement of its written words is key to the way the story is delivered. Aliens, to return to a prior example, wouldn’t work as well in a novel that lacks the emotion injected by the actors’ voices and expressions. Which finally takes me to video games, which are unique among media types for directly involving player input. Yes, there are choose-your-own-adventure books and experiments like Bandersnatch, but those are the exceptions, rather than the norms. A video game requires player input to proceed, and may even tell different stories depending on how they are played. This means that the audience, the players, interact with games in a way that is inherently different from how they interact with other forms of media like books and television. And while there are wonderful ways to take advantage of this concept (Metal Gear Solid and Undertale were both famous for how they took advantage of the medium), it also makes a specific type of story much harder to tell in videogame format: Satire.

I love satirical films, those that purposefully make their points by pretending to be another genre and making fun of its points. Scream and Scary Movie both took the piss out of many classic horror tropes and succeeded in building hilarious movies that were, in and of themselves, competent horror movies. (And the fact that one of these directly parodied the other only makes the entire thing more impressive.) Starship Troopers, to finally hit the dreaded point, makes its satire so glaring and obvious that its scathing commentary on militarism and fascism should be obvious. But that movie, one of the best works of satire in the medium, hits the fascinating problem of people just mistaking the intentional satire for bad filmmaking, and interpret it as a cheesy sci-fi war movie. That’s a movie that hits you in the face with a sledgehammer labeled “get the joke?” and then does it again and again by pointing at all the ways the cheery characters don’t notice they live in a totalitarian hellscape. And even though it’s the perfect medium for the work, some people still miss it because they just see the kind of cool action sequences and get caught up in wanting to do the cool thing.

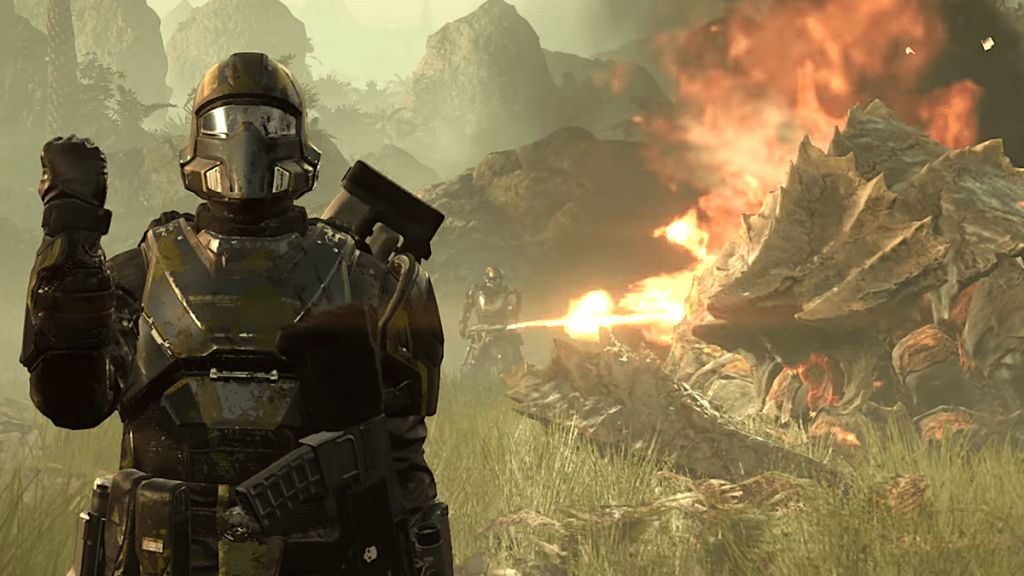

To stop beating around the bush, this article is about Helldivers 2, the latest flavor of the month co-op game that is probably going to fall out of the public consciousness by the summer. It is (despite there being an actual Starship Troopers game) very much just a Starship Troopers game, using a lot of the same techniques the film does in its presentation to paint a picture of a fascist military hellscape where everybody is happily along for the ride and unaware of what genre they’re living in. And I love it when the actual movie does this, but players engage with games differently than they do with movies. There’s a difference between watching film characters passively and getting the joke, than in playing the role of those characters and getting lost in the fun gameplay. I listen to people play it and, with or without any irony, shout out the same catchphrases as the comically brainwashed characters, because they’re playing a game and having a good time doing it. Obviously this isn’t a “video games cause violence” rant, because they don’t, but it is still a work of media that is espousing something, and players need to be aware of that. Even if the intent of the work is to make a fun satire, the game is a game, meaning that players engage by accepting the roles of the soldiers that don’t realize what world they live in, fighting for the false cause, and listening to the propaganda phrases on a loop while having fun. It seems like a fun game, and that is part of why I don’t like it. When you make the characters in Fight Club and Wolf of Wall Street too cool, people miss the point by just observing them. When you make playing along in the fascist hellscape too much fun, people who are being asked to play roles in the story are almost guaranteed to miss the point, listening to the funny propaganda phrases and subconsciously accepting them while they have fun. It could be harmless, or it could be the start of a pipeline because the way we engage with the “joke” propaganda is now completely different; it requires us to internalize and act upon it.

As I said earlier, I’ll never tell somebody not to engage with a work. Again, Helldivers looks fun, and I can’t argue against team horde shooters when Left 4 Dead 2 is one of my favorite games. But as we see media literacy dying on the internet, it does make me worry, and I so I just ask that people remember what they’re playing and engage critically. Enjoy your games and shoot some bugs, just remember what kind of game you are playing and that you are casually injecting the ideology into your head by never thinking about it. The first step to accepting something is to not think about it and let the phrases become commonplace. And as I said, it’s our duty as the audience to be aware of what we take in.